Debussy: La Boîte à Joujoux

Expected to ship in 2-3 weeks.

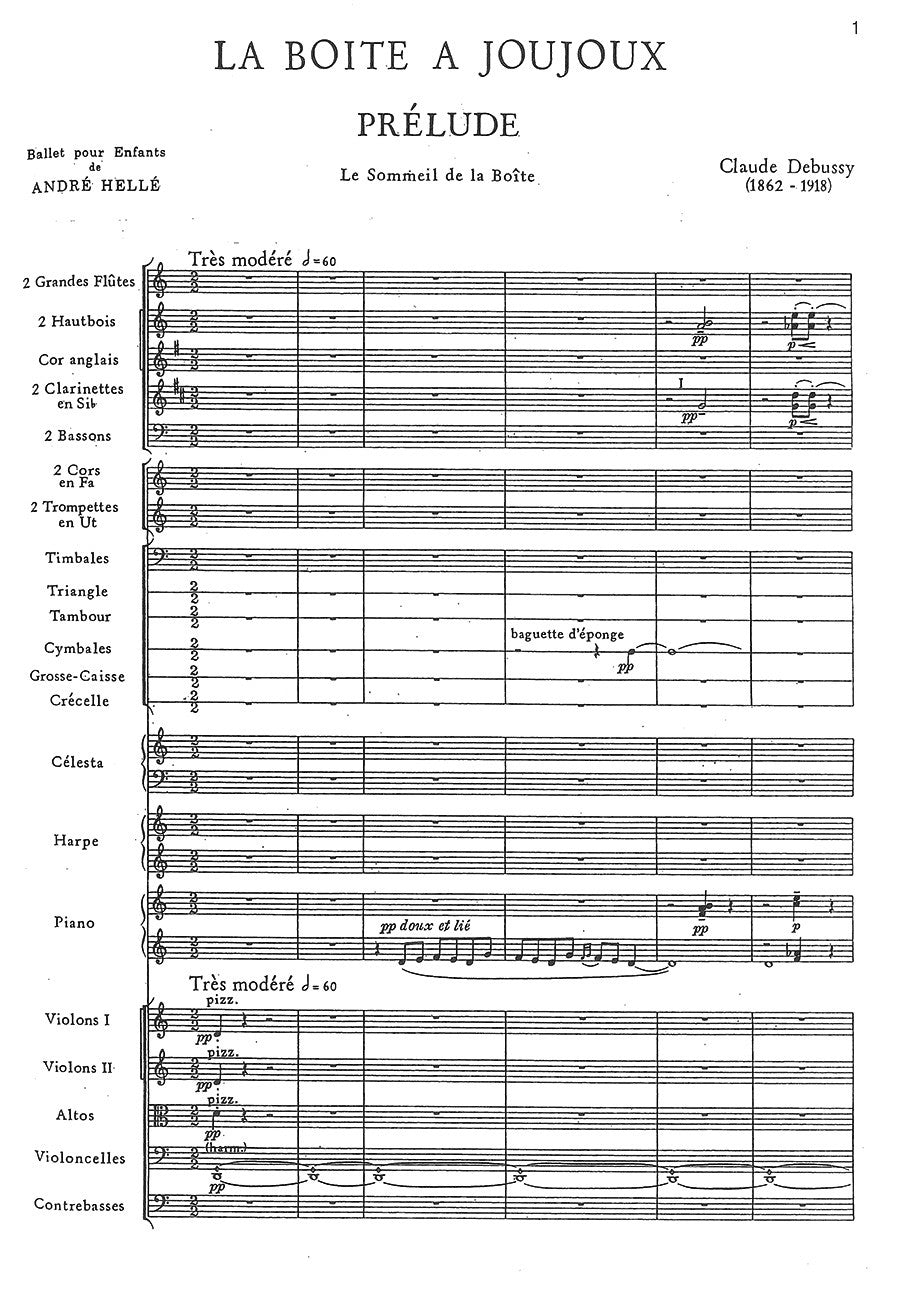

- Composer: Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

- Arranger: André Caplet (1878-1925)

- Format: Full Score

- Instrumentation: Orchestra

- Work: La Boîte à Joujoux (1913)

- Size: 8.3 x 11.7 inches

- Pages: 160

Description

Following the completion of his ballet Jeux, poème dansé (1913), Debussy set to work on a new musical game, for which he drew on his unique understanding of children's toys and children's music developed during his previous compositions. with his piano album, Children's Corner (1908), published by Durand and dedicated to his daughter Claude-Emma (born 1905), usually called Chou Chou, Debussy now set to musically depicting an illustrated children's story by the established children's author, André Hellé (1871–1945), La Boîte à Joujoux (The Toy Box). Debussy provided an overview of Hellé's story, as follows: ‘a cardboard soldier falls in love with a doll; he seeks to prove this to her, but she betrays him with Polichinelle. The soldier learns of her affair and terrible things begin to happen: a battle between wooden soldiers and polichinelles. in brief, the lover of the beautiful doll is gravely wounded during the battle. The doll nurses him and… they all live happily ever after.' (Debussy, in an interview in Comoedia (1 February 1914), reproduced in Lesure, 1977, 307–308).

The story is that of a love triangle. A toy soldier falls in love with the dancing doll, however, the doll has fallen for Polichinelle (a traditional French comic clown-like character, often called Pulcinella). A war breaks out between the soldier and Polichinelle. Unfortunately the soldier is hurt, but as the doll cares for him she falls in love with him, turning around the soldier's fortunes for a happy ending, in which the doll and soldier marry. The depth of these characters is revealed by Hellé, who noted that the toy box is representative of ‘real towns in which the toys live like real people.' (Thompson, 1940, 358).

In the same interview with Maurice Montabré in 1914, Debussy spoke about the staging of the work: ‘There is talk of putting on La Boîte à joujoux at the Opéra-Comique. That most perfect of designer Hellé has conceived the set and staging, and it is through the enthusiasm of M. Gheusi that the project has got off the ground. But it will be very difficult to mount. The Opéra-Comique is only a theatre, and for this work the setting and conditions for performance must be just right. You know what it is, don't you? […] a work to amuse children, nothing more.'

Debussy's emphasis on a children's audience, and his reference to its ‘simplicity', is at odds with the complexity of the work and the detail of its score which suggests he placed as much of his usual artistry in this work as he did in his opera Pelléas (1902). Although La Boîte à Joujoux was not performed in Debussy's lifetime he gave a detailed insight into his idea of the staging of the ballet. He wished to ensure that the work's ‘natural simplicity' was projected via characters using ‘angular movements' with a ‘burlesque appearance', though he had clear reservations about using the Opéra-Comique.

Ernest Newman (1918, 346), in his exposé on Debussy's style, compared La Boîte to his opera Pelléas, in noting the atmospheric similarity between the toy shop and the woods in Pelléas. This remarkable comparison is in stark contrast to Debussy's intentions who mocked Gheusi's theatrical plans in a letter to Durand by comparing them to Pelléas: ‘I'm sure you're aware of M. Gheuzi's generous, if curious, ideas for La Boîte à Joujoux? They're characteristic of our times, in which it's the thing to make much ado about nothing at all!' (Debussy, Letter to Durand, 16 January 1914, in Debussy Letters, ed. Francois Lesure and Roger Nichols, London: Faber and Faber, 1987, 285).

The play on Shakespeare creates a further literary comparison and sets up a mocking tone. It is worth seeking to explore Debussy's tone here: his reference to ‘nothing' exposes his other comments that the work be simple, and childlike. Nonetheless his previous remarks outlining the role of the doll and its relation to his opera projects a detailed dramatic intention for this work: ‘The soul of a doll… is more mysterious then even Maeterlinck supposes; it does not readily put up with the clap trap that so many human's put up with.' (Debussy, Letter to Durand, 27 September 1913, in Debussy Letters, ed. Francois Lesure and Roger Nichols, London: Faber and Faber, 1987, 278).

Debussy wanted marionettes and simple movements, rather than real ballet dancers, for the characters, yet using traditional balletic gestures. Prime among Debussy's concerns is that La Boîte à Joujoux remains ‘unaggressive' and that it be presented in ‘some fairly novel manner.'

Publishers use a lot of words to describe what they sell, and we know it can be confusing. We've tried to be as clear as possible to make sure you get exactly what you are looking for. Below are descriptions of the terms that we use to describe the various formats that music often comes in.

Choral Score

A score for vocalists that only contains the vocal lines. The instrumental parts are not there for reference. Generally, cheaper than a vocal score and requires multiple copies for purchase.

Facsimile

Reproductions of the original hand-written scores from the composer.

Full Score

For ensemble music, this indicates that the edition contains all parts on a single system (there are not separate parts for each player). In larger ensembles, this is for the conductor.

Hardcover

Hardbound. Generally either linen-covered or half-leather.

Orchestral Parts

Similar to a wind set, this is a collection of parts. In the case of strings, the numbers listed are the number of copies included, though generally these are available individually (often with minimum quantities required).

Paperback

When publishers offer multiple bindings (e.g. hardcover) or study scores, this is the "standard" version. If you're planning to play the music, this is probably what you want.

Performance / Playing Score

A score of the music containing all parts on one system, intended for players to share. There are not separate parts for each player.

Set of Parts

For ensemble music, this indicates that there are separate individual parts for each player.

Solo Part with Piano Reduction

For solo pieces with orchestra, this is a version that contains a piano reduction of the orchestra parts. For piano pieces, two copies are typically needed for performance.

Study Score

A small (think choral size) copy of the complete score meant for studying, and not playing. They make great add-ons when learning concertos and small chamber works.

Vocal Score

A score prepared for vocalists that includes the piano/organ part or a reduction of the instrumental parts.

Wind Set

For orchestral music, this is a collection of wind and percussion parts. The specific quantities of each instrument are notated.

With Audio

In addition to the printed music, the edition contains recordings of the pieces. This may be an included CD, or access to files on the internet.

With / Without Fingering (Markings)

Some publishers prepare two copies - a pure Urtext edition that includes no fingering (or bowing) suggestions and a lightly edited version that includes a minimal number of editorial markings.