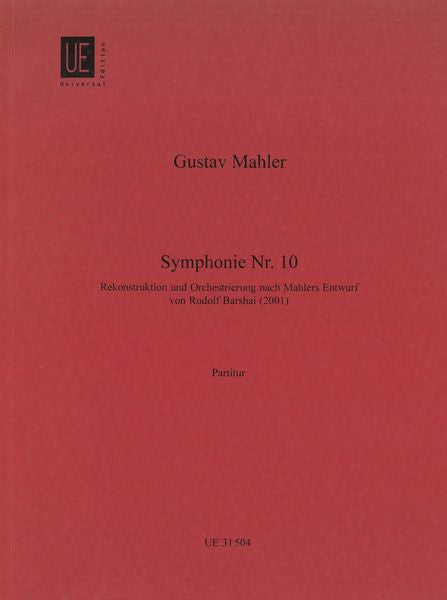

Mahler: Symphony No. 10

Expected to ship in 1-2 weeks.

- Composer: Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

- Editor: Rudolf Barshai

- Format: Study Score

- Instrumentation: Orchestra

- Work: Symphony No. 10 in F-sharp Major

- ISMN:

- Size: 6.7 x 9.4 inches

Description

Bernd Feuchtner

A New Image of Mahler

What the Tenth Symphony has gained from Rudolf Barshai

The reason why Mahler's Tenth appears so seldom in concert programmes is because the composer was unable to complete it – of the five movements, three exist only in the form of sketches and a structural framework. To be sure, these were very commendably deciphered and edited by Deryck Cooke in the 1960s, so that performances of the symphony with full orchestra can take place. Nevertheless these have always left behind a certain feeling of unease, on account of the dissatisfying overall impression. The sound lacked body and weight, the overall form lacked plasticity.

The musical material shows that the Tenth represented a further step forward for Mahler. in the first Scherzo he breaks free of rhythmic limitations in the manner of Stravinsky or Berg, as he playfully turns folk-like materials into the music of the future. Like Berg's Wozzeck , too, the symphony is conceived as an arch structure. Two great Adagios in sonata form enclose two vehement scherzos, separated from one another by the fulcral point of the brief Purgatorio.

And from here onwards, without a doubt, the Second Viennese School can be glimpsed in the near distance. Mahler is here so far advanced that, as with his followers, one can no longer say whether a second or a seventh is a dissonance. This is why one should avoid any deviation from Mahler's sketches. When deciphering his difficult handwriting, there is a temptation to smooth out harmonies which would be better left rough. But it is only when the harmony remains ambiguous that certain passages begin to sound truly diabolical. and in this symphony it certainly is a question of the devil – he now manifests himself in his full monstrousness. Rudolf Barshai conducted the Tenth with the Austrian Radio Orchestra at the end of the 1980s, in Vienna and Montpellier, but soon discovered that the dissatisfaction he felt could not be dispelled by a few corrections here and there. Changing details was pointless: he had to make his own revision. The Cooke version remains the ground plan and preparatory work, but the Barshai version has given the Tenth a new shape which comes a step closer to Mahler's intentions.

Mahler's annotations in the sketches of the Tenth are of a personal, indeed intimate nature. Much more important – because referring to music – are quotations of a musical nature, or a citation from Bach. Like some of Mahler's other symphonic movements the Purgatorio – which he had already completed – is derived from a song, in this case Das irdische Leben. This had been a parable of the ‘way of the world' – in which human needs are not satisfied, but postponed systematically. in the Symphony it is placed at the service of higher thoughts. The symphonic presentation of these grand thoughts demands the rich, full-bodied Mahler orchestra with its sonority dominated by the strings, not sketchy lines. Several passages in the first movement sound empty because they are incomplete, and here it is possible to conceive of several different ways of completing them: we can see traces of attempts at improvement in Mahler's own hand. for example, the last semiquaver of bar 101 gives rise to parallel octaves, strictly forbidden by the laws of harmony and here caused by Mahler's overwrought mental state. Cooke did not correct this passage, an omission which to a certain degree brings dishonour on a great composition. It is one of the main advantages of Barshai's revision that it does not shirk such questions. Moreover he makes extensive use of such typical Mahler fingerprints as the confrontation of fortissimo and pianissimo in different instrumental groups at the same time – e.g. at the climax of the Adagio in the Ninth, where the strings deploy their full power while the wind double the melodic line pianissimo. This Mahlerian invention leads to fantastic effects and naturally had to be used in the Tenth as well. A similar effect thus occurs at bar 153, where the oboe plays piano espressivo and the second violin pp ohne Ausdruck (‘without expression'), giving rise to a decisive difference in timbre.

In the second movement Rudolf Barshai exploits above all else Mahler's innovations in the treatment of percussion. The last four bars in particular demonstrate unusually rich percussion scoring. At the beginning of the fourth movement, however, and throughout this movement in general, quite different principles of instrumentation apply, as they do in the fifth movement. These movements should provide fertile soil for musicological research. There is certainly a relationship between the second Scherzo and the mockery of ‘this putrid plaything of an earth' in the first movement of Das Lied von der Erde, but the Scherzo goes much farther. Mahler's annotations here (‘the devil dances with me') really are intended programmatically. The devil even plays the dandy, the better to play the seducer. This must be made to sound truly sensual.

Cooke's intention was to make the sketches audible; Barshai's reworking attempts to exploit the full sound of the Mahler orchestra, which in this version sounds as wholeheartedly involved as in Mahler's other symphonies. in Cooke's version of the second Scherzo, for example, Mahler's prominent bass line with the movement's principal rhythmic idea at bar 157ff is entrusted only to a solo trombone marked forte, which sounds rather grotesque. Moreover the shortening of the note values creates a scherzoso feel. in Barshai's view, however, this theme gives an decisive thrust of energy towards the movement's climax, and is thus allocated to all bass instruments and bass trombone, playing markig (‘energico') and in Mahler's original note lengths.

The finale contains several passages which are particularly hard to decipher. in this tonally free context Mahler was not always wholly consistent in his use of accidental signs. Here the editor's task was both to make the motifs recognisable and to avoid harmonic triteness: only then does the sense become clear. Between bars 53-55 in Cooke's version the harmony becomes extremely trite, because as a result of one unclear note he more or less criminally perverted the harmony into in E-flat Minor, thereby transgressing against Mahler's philosophy on the most fundamental level. What confused Cooke was the fact that in bar 54 the melody of the upper strings contains a G-flat, conflicting harshly with the G natural of the E-flat Major in the first and second parts – a great, elemental harmonic conflict which gives rise to a painful dissonance. But when it comes to Mahler, textbook harmony proves inadequate.

Additionally, in Cooke's version this passage produces a melancholy effect – an attitude which is so utterly incompatible with Mahler's philosophy. But there is also, in the fifth voice here, another note which is unclear in Mahler's manuscript, which could be read as C-flat. Barshai however inclines towards reading it as D-flat, which creates a significant transformation of the mood of the whole passage, indeed brings it to life. Now we find ourselves in A-flat Major, and specifically on the dominant seventh chord of this key – already on the path of harmonic tension leading to F-sharp Major, which soon arrives with a compelling sense of inevitability. Thus if one does not take Mahler seriously here, then there emerges either that kind of sugary sentimentality which was alien to him, or instead a kind of hopelessness which accords equally little with what we know of or about him. An equally significant difference can be found at bar 155. in bar 390 a serious error escaped Cooke's notice, when he requires basses and contrabassoon to play E-sharp rather than E natural, thereby regrettably eliminating a harsh dissonance.

The end of the symphony should at no cost sound bittersweet – rather, it alternates between bitterness and repose. Mahler does not abandon all doubt, and for that reason the music must hurt in places. Eleven bars before the end Cooke read a bass note as F-sharp, which however read as E-sharp acquires an added bite. As an unprepared suspension it sets up a powerful tension which is not resolved until the magical close. The melody which follows is also placed in a new light. Barshai hears this as a quotation from Schubert and thus gives it to the trombones to be played with solemn devotion. Then, after two, rather hesitant, bass clarinets there erupts a great explosion like an earthquake, followed by a diminuendo before the eternal rest of F-sharp Major. The noted Mahler expert Jonathan Carr found himself particularly impressed by the unexpected tension which the last twenty minutes of the score gain thanks to Barshai's revision.

Such refinements, which of course critically determine the overall musical form, could only have become first apparent to a musician like Rudolf Barshai, who has devoted his life to the interpretation of the great European symphonic tradition and lived with Mahler's music for several years.

Bernd Feuchtner

Publishers use a lot of words to describe what they sell, and we know it can be confusing. We've tried to be as clear as possible to make sure you get exactly what you are looking for. Below are descriptions of the terms that we use to describe the various formats that music often comes in.

Choral Score

A score for vocalists that only contains the vocal lines. The instrumental parts are not there for reference. Generally, cheaper than a vocal score and requires multiple copies for purchase.

Facsimile

Reproductions of the original hand-written scores from the composer.

Full Score

For ensemble music, this indicates that the edition contains all parts on a single system (there are not separate parts for each player). In larger ensembles, this is for the conductor.

Hardcover

Hardbound. Generally either linen-covered or half-leather.

Orchestral Parts

Similar to a wind set, this is a collection of parts. In the case of strings, the numbers listed are the number of copies included, though generally these are available individually (often with minimum quantities required).

Paperback

When publishers offer multiple bindings (e.g. hardcover) or study scores, this is the "standard" version. If you're planning to play the music, this is probably what you want.

Performance / Playing Score

A score of the music containing all parts on one system, intended for players to share. There are not separate parts for each player.

Set of Parts

For ensemble music, this indicates that there are separate individual parts for each player.

Solo Part with Piano Reduction

For solo pieces with orchestra, this is a version that contains a piano reduction of the orchestra parts. For piano pieces, two copies are typically needed for performance.

Study Score

A small (think choral size) copy of the complete score meant for studying, and not playing. They make great add-ons when learning concertos and small chamber works.

Vocal Score

A score prepared for vocalists that includes the piano/organ part or a reduction of the instrumental parts.

Wind Set

For orchestral music, this is a collection of wind and percussion parts. The specific quantities of each instrument are notated.

With Audio

In addition to the printed music, the edition contains recordings of the pieces. This may be an included CD, or access to files on the internet.

With / Without Fingering (Markings)

Some publishers prepare two copies - a pure Urtext edition that includes no fingering (or bowing) suggestions and a lightly edited version that includes a minimal number of editorial markings.